John Brown

in Chambersburg, PA

On The Run

On the run for the murders of five pro slavery settlers in Kansas in 1856, abolitionist John Brown rented rooms in a boarding house in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania during the summer and fall of 1859 where he planned a raid on the Federal Arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. If his plan succeeded, he and his followers would collect enough guns to equip an army of slaves and incite them to rebel. If his plan failed, he would be hanged.

Brown married twice and fathered 20 children. He moved frequently, became involved in many business ventures, and was forced to declare bankruptcy in the 1840s. Through it all, Brown supported the abolition of slavery and came to the conclusion that the only way to end slavery was to lead a war against it himself.

May, 1856

In May 1856, Brown, his sons, and a small band of sympathizers murdered five pro-slavery men in an event that is known as the Pottawatamie Massacre. Brown spent the next two years on the run while gathering money and arms for his cause. In the summer of 1859, Brown came to Chambersburg. Using the assumed name of Dr. Isaac Smith, Brown occupied a bedroom in the upstairs of Mary Ritner’s Boarding House on East King Street and planned his attack on the Federal Arsenal at Harpers Ferry.

Mary Ritner Boarding House in Chambersburg, PA

Brown meets Frederick Douglass

During his stay in Chambersburg, Brown met with abolitionists including the famous anti-slavery author and lecturer Frederick Douglass. Even though Douglass was opposed to Brown’s plan to create a slave uprising, he met with Brown at an old stone quarry outside of Chambersburg in August 1859. Brown was unable to convince Douglass to join the raid on Harpers Ferry, and Douglass fled to Canada briefly to avoid being implicated in the raid.

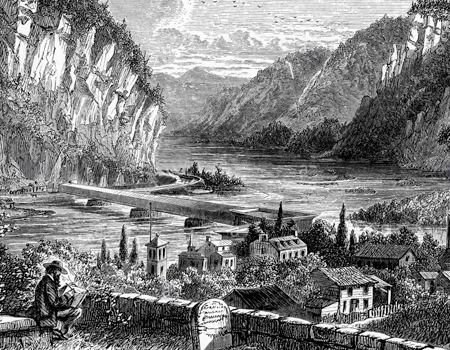

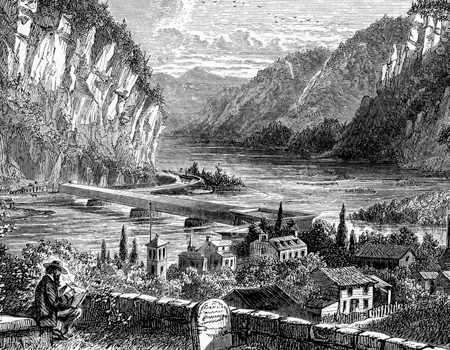

Harpers Ferry, WV

John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry.

Brown sent the weapons that he had been stockpiling in Chambersburg to the Kennedy farm. Just over the Maryland border, the Kennedy farm was close to Harper’s Ferry and it was the staging point for the attack.

October 16, 1859

On Sunday evening, October 16, 1859, Brown and 21 of his supporters slipped into Harpers Ferry. They seized the federal arsenal, killed seven men and injured about a dozen more. When news of the attack reached Richmond, the U. S. Marines rushed to Harpers Ferry and began shooting. Brown and the few of his men who were left barricaded themselves in a small brick building and refused to surrender. Finally, a company of Marines stormed the building and captured Brown and his men.

December 2, 1859

John Brown was tried, found guilty of murder, treason and inciting a slave insurrection. He was hanged, along with nine of his followers, on December 2, 1859 in Charles Town, Virginia.

The Great Fire of 1864 | The Burning of Chambersburg

As the likelihood of a Confederate victory waned, the harsh impacts of war in the south destroyed mills, crops, barns, and warehouses. On July 28, 1864, General Jubal Early issued the order to General John McCausland to ransom Chambersburg for $100,000 in gold or $500,000 in Yankee currency as retaliation for Northern devastation of the Shenandoah Valley. As Confederate troops closed in on the Mason Dixon Line and its northern target of Chambersburg, General Darius Couch, who commanded the Headquarters of the Department of the Susquehanna at Chambersburg, worked to evacuate military supplies from the town. A small unit of Union soldiers secreted themselves in the hills along St. Thomas, surprising the McCausland column of Confederates and holding them back a few more hours to allow Couch to liquidate the army headquarters.

By daybreak, Confederate soldiers had positioned cannons atop the hill west of Chambersburg. About 5:30 AM, they fired on the sleeping town, rode into town, and rang the courthouse bell to gather residents to hear the ransom demand. According to an account by Chambersburg shopkeeper Jacob Hoke, <

“The money demanded was not, and could not be paid, for the reason that there was nothing like the amount demanded remaining in the town. Besides the citizens did not feel like contributing aid in the overthrow of their government.”

Once it was clear to Confederate troops that the ransom would not be paid, they wasted no time in setting the fires. By day’s end, over 550 structures had burned, 2000 people were homeless, and more than $750,000 in property was lost.

Hoke described the column of smoke created by the town’s burning as a crown of sackcloth, asserting, “It was heaven’s shield mercifully drawn over the scene to shelter from the blazing sun the homeless and unsheltered ones that had fled to the fields and cemeteries around the town, where they in silence and sadness sat and looked upon the destruction of their homes and the accumulation of a lifetime.”

The Great Fire of 1864 | The Burning of Chambersburg

As the likelihood of a Confederate victory waned, the harsh impacts of war in the south destroyed mills, crops, barns, and warehouses. On July 28, 1864, General Jubal Early issued the order to General John McCausland to ransom Chambersburg for $100,000 in gold or $500,000 in Yankee currency as retaliation for Northern devastation of the Shenandoah Valley. As Confederate troops closed in on the Mason Dixon Line and its northern target of Chambersburg, General Darius Couch, who commanded the Headquarters of the Department of the Susquehanna at Chambersburg, worked to evacuate military supplies from the town. A small unit of Union soldiers secreted themselves in the hills along St. Thomas, surprising the McCausland column of Confederates and holding them back a few more hours to allow Couch to liquidate the army headquarters.

By daybreak, Confederate soldiers had positioned cannons atop the hill west of Chambersburg. About 5:30 AM, they fired on the sleeping town, rode into town, and rang the courthouse bell to gather residents to hear the ransom demand. According to an account by Chambersburg shopkeeper Jacob Hoke, <

“The money demanded was not, and could not be paid, for the reason that there was nothing like the amount demanded remaining in the town. Besides the citizens did not feel like contributing aid in the overthrow of their government.”

Once it was clear to Confederate troops that the ransom would not be paid, they wasted no time in setting the fires. By day’s end, over 550 structures had burned, 2000 people were homeless, and more than $750,000 in property was lost.

Hoke described the column of smoke created by the town’s burning as a crown of sackcloth, asserting, “It was heaven’s shield mercifully drawn over the scene to shelter from the blazing sun the homeless and unsheltered ones that had fled to the fields and cemeteries around the town, where they in silence and sadness sat and looked upon the destruction of their homes and the accumulation of a lifetime.”

Franklin County Visitors Bureau

Explore Franklin County PA is the official site for adventure, history, and getaways throughout our wonderful county. You'll find adventure at your pace throughout our diverse and unique towns of Chambersburg, Greencastle, Waynesboro, Mercersburg, and a little sliver of Shippensburg and all points in between.

Underground Railroad

Underground Railroad